Women are fighting. In every field, in every area of life. We are fighting in the cinema, we are fighting for the right to make decisions about our lives and we are fighting for social issues. As an experienced woman over fifty I can guarantee one thing: We won't give in. Ever.

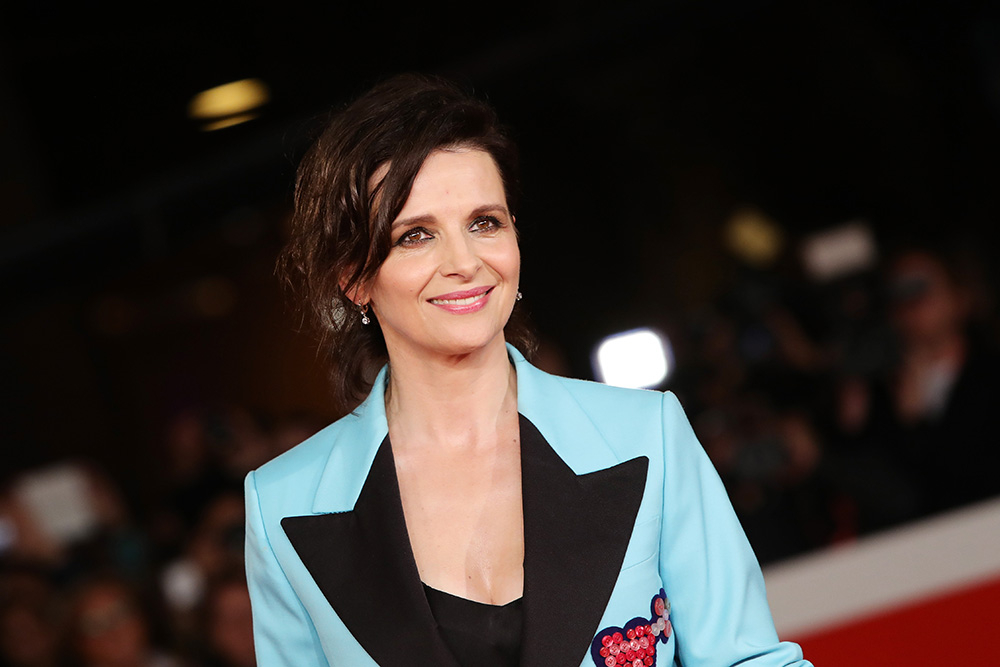

Not so long ago, the film industry was said to have no roles for actresses over fifty. But you appear every year in many famous productions. Poland has recently seen the release of the comedy Baby Bump(s), and we are waiting for the premiere of yet another film in which you play the leading role – Let the Sunshine In by Clair Denis. Are you an exception or has there been a change in the film industry?

I wouldn't call it a revolution and I wouldn’t say that the cinema has suddenly started to be particularly open to people my age. I’d rather call it ‘a process in progress’. It has to do with cinema’s slow departure from showing only the good-looking women, those who are young, pretty and attractive. Today, there must be a story behind the characters in order to hold viewers’ attention. Things were different fifteen or twenty years ago.

What instigated the process you are talking about?

There has been a digital revolution. You can find everything on the internet now, so viewers who used to go to the cinema just for the sake of watching something no longer need to leave their houses. All they have to do is type the relevant words in their search engine and they can easily watch films as much as they please. People who still go to the cinema these days are those who want to see a character with a certain experience or a certain story to tell. From this viewpoint, the age of actresses from my generation, me included, is an asset. We have a fair deal of experience, so we have more stories to tell and act out than actresses who have just entered the profession.

Directors, and film producers in particular, like showing young women in their films because they can count on them to attract young viewers to the cinemas and, as we know, those people form the biggest target group. However, judging from the scripts I get to read, the situation is improving with each year. This is partly thanks to the growing number of active women directors.

France is leading the way in that respect.

That’s true. We stand out against other countries. But let's be honest: is 25 per cent really that much? Especially given the fact that women constitute 52 per cent of France's population? These proportions, in my opinion, don’t give us reason for joy yet. We can be glad that there is indeed a process which brings about changes. We have to make sure it runs smoothly and doesn't turn in a wrong direction.

In which direction, for instance?

Women need to remain independent; they have to develop their own language. Women auteurs should have their own style. I have witnessed many situations when female directors were trying to copy men, to behave on the set like men, to make films like men. The point is not to let more women into the cinema world and then see them make films like men and behave like men. The point is to reconstruct this world, to uncover those elements that have so far been hidden, and to talk about it with a new sensitivity.

We have problems with that even at the most basic level as modern cinema equipment, like 3D cameras or special effects, is inseparably associated with men. If women want to change it, they have to distinguish themselves as auteurs.

Do you like 3D and special effects?

I’m rather a fan of the analogue cinema, but I like to get a taste of special effects and other technological wonders from time to time. That's why I accepted roles in films like Godzilla by Gareth Edwards. Normally, though, technological revolutions don’t appeal to me. Perhaps because I myself see the world more in 2D than in 3D.

What do you mean?

I have been painting since I was a child. That's how I express myself. Ever since I can remember, I have always had a pencil and crayons in my hand. My mother noticed my passion. She painted herself, so she knew in which direction she should encourage me to go in order to develop it. I have always cultivated my acting alongside my painting. I’ve never given up one for the other.

Not long ago, I even had a chance to combine both these passions in Words and Pictures by Fred Schepisi. I played an artist and my own paintings appeared on the set. The director praised them immensely. In Ghost in the Shell by Rupert Sanders, a film based on a classic Japanese manga, I played a scientist. That's something I am very happy about. I am proud that the word ‘scientist’ ceases to be associated exclusively with men. This really benefits the process of changing the image of women.

In what way?

I have the impression that we are becoming less dependent on men’s eyes and how they see us. The camera does not focus on our bodies, but on our actions and on what we represent. Female and male characters are becoming equal. We no longer copy the 19th-century literary myth that requires the romantic heroine to wait for her rescuer.

My characters are independent; they can take care of themselves. This also applies to my latest film, Let the Sunshine In by Clair Denis. [In Polish cinemas from 8th June; Editor's note.] But it is not like this everywhere. Art film is much bolder in this respect. I remember my role in Camille Claudel 1915 by Bruno Dumont – I had absolutely no makeup on, and note that I was almost fifty at that time. At first, I couldn't get used to the fact that my wrinkles and imperfections weren't hidden behind the layers of cosmetics. But I soon used my head and thought to myself: “What do I care? At worst, the cameraman will have more work with the lighting, but that's not my problem!”

How did you feel then?

I felt emancipated. I learned an important lesson. Today, I don't feel shame or embarrassment if I don't wear makeup. After all, do I put on makeup for others or for myself? Now I know that it’s for me. Therefore, I do it when I want and not, for example, when I appear on the set. I am trying to contribute to the feminisation of the cinema even in this little way. And the feminisation of the cinema is something in which your fellow countrymen and women have played a significant role.

What kind of role?

In Poland there has been a tradition of outstanding artists who understood perfectly what it means to be a woman.

Whom do you actually mean?

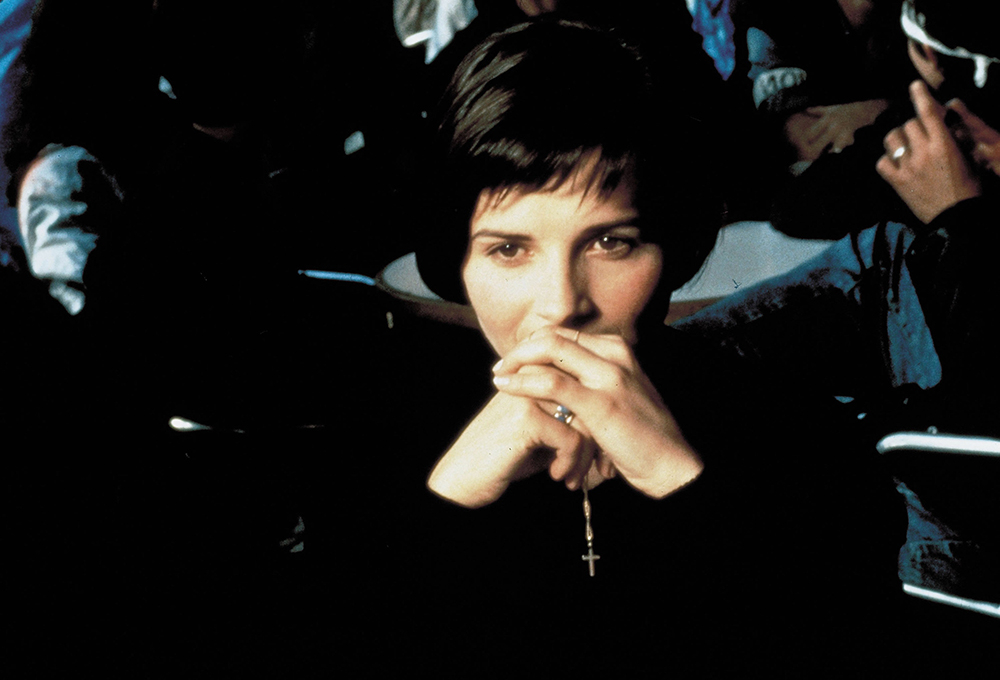

In the first place, Krzysztof Kieślowski, with whom I worked on Three Colours: Blue. He made a brilliant career in France. A lot of our filmmakers drew inspiration directly from his work. He has got a base of avid fans and the number of his followers has never fallen. He was able to step into women's shoes; he was infallible in understanding what it means to be a woman in a world dominated by men. He was able to examine this issue from a very broad perspective and to relate it to historical processes. He knew that our current situation has its roots in the past.

Throughout history, women have been denied access to any power. I believe, and so did Krzysztof, that this was the way men were trying to make up for their inability to give birth to new life. Let's take religion, say. We don't have women priests, and God is always presented as a man. Fertility goddesses, once so adored, completely disappeared from monotheistic religions. Governments, too, are dominated by men. Where have all the women gone? Who said God was a man? Excuse my tone, but when I talk about it and when I realise how absurd it is, my blood pressure immediately goes up.

How do you remember Kieślowski?

He was an exceptionally sensitive director and one open to dialogue. He could talk about anything, even about very personal issues. This is most certainly the reason why he was able to get the best from his actors. You didn't have to make special efforts to show your best side. He himself could see the most interesting things an actor could offer. What is more, he knew how to capture them on screen. It's the same with love: You can't push it; you have to agree to it. It's very difficult to find the right words for what I am trying to express. It's always like that when you talk about emotions. The process which takes place between the actress and the director is so interesting because it is based on what you feel, on something that is impossible to express verbally. Krzysztof and I influenced each other very strongly, and this resulted in a wonderful film. I do not at all regret turning down a role in Jurassic Park to play in Blue.

So that’s what happened?

Steven Spielberg offered me a role in his film after I had spoken with Kieślowski. I can't back out in such a situation. I feel honour-bound. I even joked with Spielberg about this and told him that I might have changed my mind only if he had given me a dinosaur or had cast me as one.

Prior to this I had always wanted to work with Kieślowski. I was due to appear in The Double Life of Veronique, but, eventually, it was Irene Jacob who played the role. At that time, I was already bound by Leos Carax's film The Lovers over the Bridge. I remember very well my first meeting with Krzysztof in a café in Paris. We soon found common ground. We laughed at life and at things we had experienced. He would say he was a pessimist, and he would call me too much of an optimist. He was very warm, kind and friendly. But he could be firm, too. When I asked him to reschedule the shooting of The Double Life of Veronique, he replied without even blinking that there was absolutely no way of doing this. For him, art was always at the top. I always considered him my mentor and friend, despite the fact that I didn't know him well. It sometimes happens that you meet someone and feel as if you have known them your whole life. That’s how it was with Krzysztof.

Perhaps it was your Polish descent that influenced the way your meeting with Kieślowski unfolded?

No, it wasn't like that. It could have been if I had met Krzysztof ten years earlier, because for many years Poland had been an imaginary country for me, a place I used to fantasise about as a little girl. At the time I met Kieślowski, though, I had a strong, real bond with Poland. As a matter of fact, it has remained strong to this day. My grandparents came from Częstochowa. I feel moved anytime I visit your country.

I remember coming to Kraków with my sister with only a backpack over my shoulder. I was 16. That was the time of Solidarity, so there was nothing to eat, no public transport, and nothing worked the way it did in France. It was a totally different world in which you could easily get lost. I thought I had landed on some alien planet. And yet, despite its strangeness, I felt that there was something familiar, something I could call my own. Poland back then seemed both rough and magnetic. To this day, I have kept the memory of being forced to fight for survival there. I made it thanks to the country’s helpful, kind and considerate people.

What sort of impression does Poland make on you today?

I am impressed by the strength of your nation. I worked with Krzysztof Kieślowski as well as with Małgorzata Szumowska, whom I consider a symbol of Polish persistence and determination in the positive sense of the words. She also shares with Kieślowski the ability to understand women perfectly. She presents them on screen in an unusual way, uncovering their intellectual sex appeal and recognising their emotional power. Szumowska is uncompromising. She doesn't give up only because others put stumbling blocks in her way. It seems to me that this is generally the strongest characteristic of both Polish women and men. You have learned from your history that you mustn't give up or hide away.

When I was taking part in the Spring Open workshop organised by Sławomir Idziak in November in Kraków, there were protests against the complete abortion ban in the whole country. Małgorzata and I supported these protests. In my opinion, the fact that so many Polish women have taken it to the streets and joined in the Black March protests proves their power, independence and persistence.

What made you support the protest?

My mother and my grandmother lived in a world in which abortion was prohibited. The stories they told were terrifying. To this day, they seem to me like the worst possible nightmare. The truth of the matter is that no ban and no person will stop a woman from resorting to abortion. If she feels that she is not able to live with the child, she will find a way of having an abortion. Unfortunately, if performed badly, the surgery poses serious risks to the patient's health and can even cause her death. The fact that such a ban is being imposed by men is, in my opinion, a gross injustice. It isn’t proof of democracy, but rather of dictatorship.

Women should have the right to decide what they do with their own bodies. It makes me very angry that somebody is trying to deprive them of that right. What I also find irritating in that whole discussion is that it is never mentioned that no woman in her right mind wants to have an abortion. No woman at all! People don't do things like that on a whim. It's the last resort. Women decide to have an abortion if they don't see any other choice. They can't be judged for that.

The fight of Polish women that you are talking about is still in progress.

Or rather: the fight of women in general is still in progress. In every field, in every area of life. We are fighting in the cinema, we are fighting for the right to make decisions about our lives, and we are fighting for social issues. Being a woman means a constant battle, every day. As a fairly experienced woman over fifty I can guarantee one thing: We won't give in. Ever. And I will take part in that battle as long as I have the strength to do so. I’m sure that Polish women won't furl their umbrellas [symbols carried by Black March protesters; translator's note]. I am their true supporter in this endeavour.

Translation Elżbieta Pawlas/Solid Information Solutions

Zaloguj się, aby zostawić komentarz.