At the V&A, an exuberant exhibition of liners – from the design of their proud prows to the frivolous, fabulous and occasionally tragic times on board.

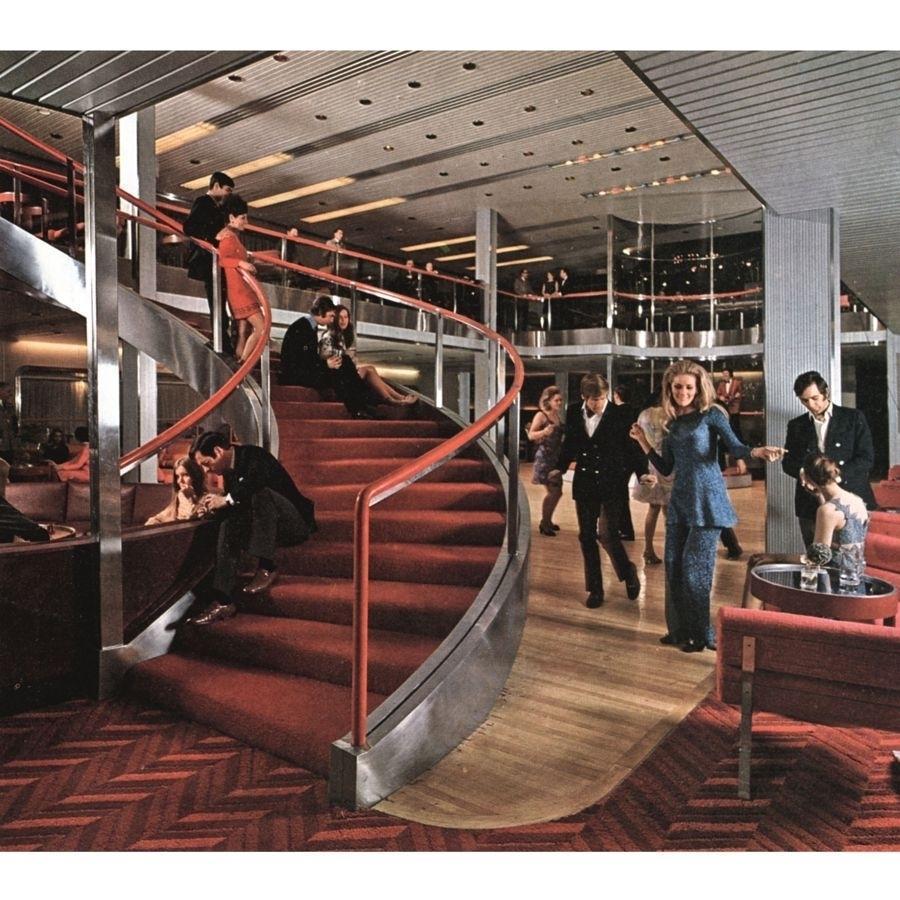

Ah! Love on the ocean wave: couples lurching across the deck before tumbling into each other’s arms; dancing in slithering satin dresses or black tie as the band plays in the ballroom; those elegant, carefree women walking down the grand stairway far above my head.

It’s the first exhibition to look at the lifestyle and the cultural significance of the liner in modernism and design - says Ghislaine Wood, co-curator of “Ocean Liners: Glamour, Speed and Style” (at the Victoria & Albert museum until 10th June).

(Photo: Williamson Art Gallery and Museum)

These are huge stories of the 19th and 20th centuries, played out through the design of liners -the curator continued - It’s about servicing the empire, about immigrants going into new lives and about what started as a service becoming one of the greatest aspirational leisure activities of the 20th century.

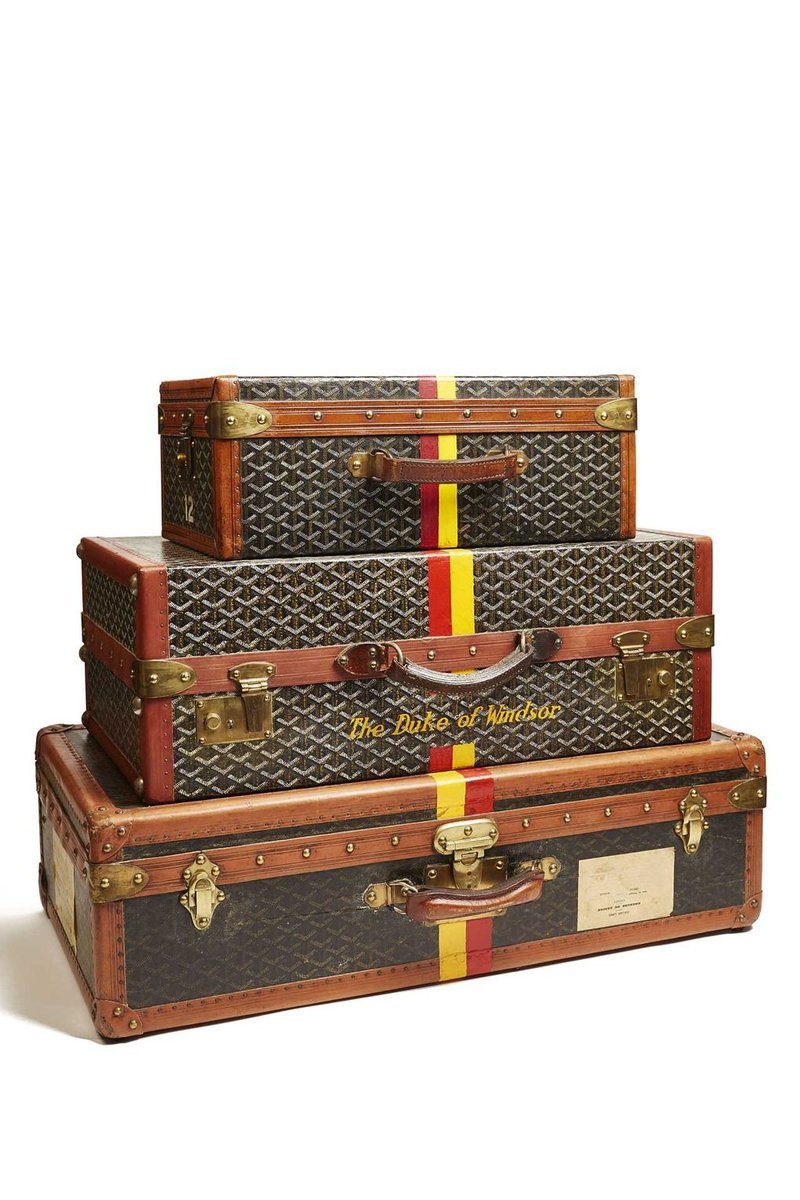

This powerful show, bringing the pounding sound of the sea to a land-locked museum, has the rare skill of being both entertaining and deeply informative. It is lighthearted in its display of the ships, their Art Deco furnishings, their luggage (the Duke of Windsor had a prime set of Maison Goyard 1940s cases), and their shivers of sadness.

A glittering Cartier tiara was saved by its aristocratic owner as the Lusitania sunk in 1915, drowning her two daughters. The memory of the Titanic is ever-present, the darkest ship tragedy of the 20th century, although the museum shows that two years later in 1914 a poster for Luna Park on New York’s Coney Island advertised the “Titanic Disaster” as its prime entertainment.

“Ocean Liners” has been seen previously in Salem, Massachusetts, and its curator Daniel Finamore, who co-curated the V&A show, points out that there is a difference between the maritime vision of England, as a seafaring island, and the wider American vision of land and sea.

To Finamore and Wood, the words of French novelist Jules Verne sum up the show’s inspiration: “The steamship is a masterpiece of naval construction: more than a vessel, it is a floating city… not merely a nautical engine, but rather a microcosm… and it carries a small world with it – all the instincts, follies and passions of human nature.”

Translating that into an informative – and even enchanting – view of life, before the arrival of aeroplanes and the Jet Set, is the purpose and the skill of the V&A exhibition. It creates an intelligent balance of historic pieces – such as the sturdy eau-de-nil coloured 1930s armchairs from the Queen Mary – with video clips of frolicking passengers in fancy hats. Throughout, there is a real sense of bringing a past era to life.

The most striking addition from our digital age, however, is not the screen of a stately vessel ploughing across the water, smoke puffing from its chimneys into the pale blue sky. The overwhelming story is of glamorous 1930s women, digitally projected to emulate a walk down the grand staircase that was a feature of the ocean liner life. (This was only, of course, for the upper echelons of society; the rest were literally lower class, not seen posing on deck, while the sailors were right out of sight below.)

The “Grande Descente”, as the walk from upper deck to lounge was known, was installed at the V&A by project curator Anna Ferrari, to give a vivid vision of those dancing years. Of the historical fashion on show, Ghislaine Wood is particularly pleased with the flapper dress by Lanvin that American socialite Emilie Busbey Grigsby donated to the V&A in the 1960s. This section of the exhibition also includes beach costumes, shown with abandon on figures whirling on sand.

The success of the exhibition is its meld of historic beauty and public enjoyment. The shapes of the vessels alone make them works of art, their slim bows cutting through the water. But with that artistic elegance, there is always a frisson of fear that the liners might, conceivably, sink – a major concern when the boats were used in 20th-century wars.

The first scene of the exhibition is departure: colourful posters designed to lure potential customers to visit, with the Cunard Line, “all parts of the world”; or to the 1935 Normandie – that floating, French Art Deco palace, with its chandeliers and pillars of Lalique glass and its idealised arrangement of society, as discussed by Finamore and Wood in the exhibition’s accompanying book.

The power, grandeur and elaboration of gold-leaf panels of Grecian athletic figures (from the first-class smoking room) is the evocation of the Normandie that Ghislaine was most proud of when the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris finally gave permission to lend this piece to the V&A.

As well as viewing the richness of the inter-war years, I watched evocative black and white films of sailors dragging luggage on to the liner, a car slung aboard by a crane, and a dense crowd, doffing hats, waving farewell to their loved ones.

(Photo: The Bruce Peter Collection)

The success of a static museum presentation – even if it incorporates film – is about the emotion that it arouses. Here the co-curators have done a fine job, and in September their exhibition will move on to the new V&A Museum of Design, Dundee – Scotland’s first dedicated design museum, appropriately in a city by the sea.

Zaloguj się, aby zostawić komentarz.